I have a new expensive habit: collecting vinyls. To the dismay of my parents, I’ve accumulated 23 total vinyls over the past year, which doesn’t seem like a lot until you calculate the total cost. They cost between $5.00 to $50.00 per (often on the larger end of that spectrum). Worse still, I have no doubt that both my vinyl collection and my total spending on vinyls will rise exponentially in this next year.

The spending is bad, but the product is arguably worse; why own a vinyl of music that can be played off other devices? My house is rigged from top-to-bottom with Amazon AI, each one in tune to Amazon Music. The televisions have access to Youtube playlists. My household has a Spotify Premium Family Plan. Paying more money for the same music is a messy investment at best and downright idiotic at worst.

Yet, I continue to buy vinyls.

Etching the Past

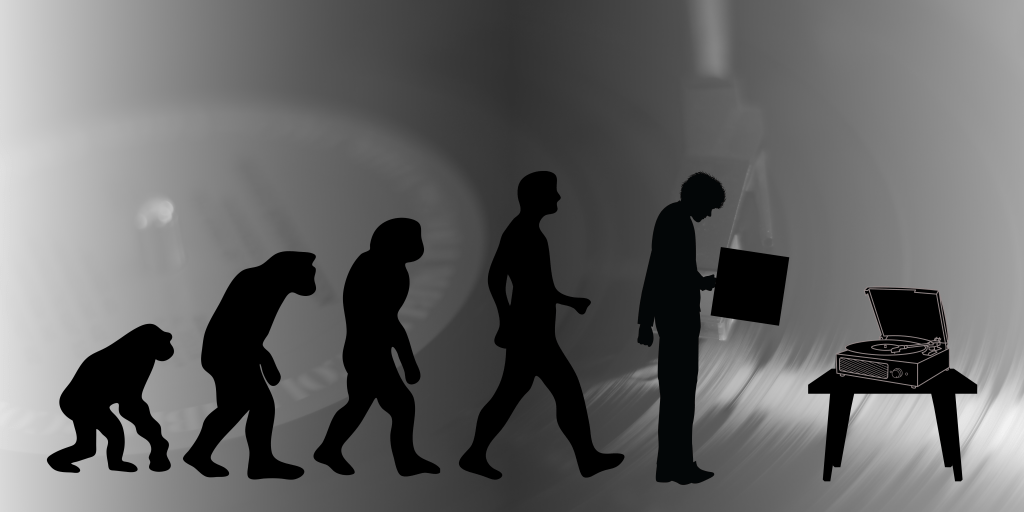

I buy vinyls because they are old. The concept of vinyl is old. The process of vinyl creation is old. Heck, looking at a vinyl record reminds you of “the good old days”.

The process: sound waves, recorded in a studio, are captured into physical grooves on 2 millimeters of disc. These grooves are jokingly meticulous (and tiny), running in a straight line from the outer edge to the center. When a stylus moves through the grooves, it mimics the original vibrations and converts them into electrical signals which, when amplified into a speaker, recreates the original sound. This process is obviously complex, and for that reason it’s considered primitive (and accounts for the ridiculous cost). Even CD’s (which are also ancient at this point) use more modern technology by use of digital sampling. In exchange for the lengthy creation process, vinyls play sounds in analog waves that directly represent the original sounds, resulting in a noticeably warmer, richer sound.

But as I said before, I don’t buy vinyls for their sound quality. I buy them because they’re old. Keeping a vinyl is like keeping a history book, and therefore I treat vinyl collection like a physical library. Imagine for one second a world where Spotify shuts down and Apple Music begins removing songs older than 100 years from its catalogues. Just like history and storytelling, music can only stay alive if it continues to be shared, and so vinyls are a method to literally etch history onto a physical surface, independent of modern digitization. The music is on the disk, able to be seen. Even without a speaker, you can move a needle along its surface and the original sound will still emerge (granted, very very quietly).

Vinyls are so old that they can even outlast us. My oldest record was an impulse buy from a mom-and-pop shop down in Morrison, CO, labelled, “ORMANDY/Philadelphia Orchestra/BERNSTEIN/New York Philharmonic” and encompasses a bunch of random tunes from 2001: A Space Odyssey. The movie’s soundtrack was recorded between 1958-1968. That’s older than my father. This thing is so old that the first conductor, Eugene Ormandy, was born in a year starting with 18, and the second conductor, Leonard Bernstein, has a posthumous biopic made after him. The oldest song on the record is The Blue Danube Waltz, Op. 314 (most recently seen in Squid Game) which is so old that its composer died the same year Eugene Ormandy was born. Some of the recordings in this disk can’t be found on any edge of Youtube, but they exist in my hand as I write this. That’s history.

Shared History

The 23 (and counting) vinyls that I have are all of my most valued artists and albums. In many ways they tell my history, from my early days of Ed Sheeran and Bruno Mars to every album of Noah Kahan, AJR, and Kendrick Lamar. Those vinyls have entrapped my personality and childhood onto a disk in the same way as if I wrote journals. I intend to pass those vinyl records on to my children, and hopefully they pass it on to theirs.

The art of the vinyl has been making a recent resurgence, and I’m glad it is. In the years it was lost in obscurity (from the 1970’s till around 2022) there has been an exorbitant amount of music, and I fear that much of it hasn’t been documented. Just recently, I scoured the internet for Eason Chan records, a famed Hong Kong singer, only to find that few were ever made and even fewer are still in circulation. To my luck, new businesses have emerged specifically in making custom vinyls; all you need are the audio tracks and designs, and you can create your own vinyl molds.

History undocumented isn’t history at all; it might as well have never happened if there isn’t any way to remember it. As expensive as vinyls are, I intend to continue collecting them (and expanding my collection into older music) because they represent the fragments of the musical world that we’ve deemed important enough to remember. And it takes active effort to keep a record (no pun intended).

Leave a comment